What is the future for ultra large container ships?

Big ships have been making the news headlines because of their sheer size. But there is much more to consider, and the argument that they bring economies of scale look shaky, writes Charlie Bartlett.

Maritime has often been taken in by the assumption that bigger is better: that is, the economy of scale.

On paper, large containerships are hyper-efficient: HMM Algeciras, at time of writing, is the largest boxship ever, and its low-speed MAN B&W 11G95ME-C engine exceeds 50% thermal efficiency. It can carry 24,000 TEU halfway across the world.

Except that it can’t.

That 24,000TEU accounts only for dimensions, not the weight, of these containers. Assuming a homogeneous 14 tonnes per container, HMM Algeciras can carry some 16,800 before it is down to its marks.

No doubt, this would be more fuel-efficient than two smaller vessels carrying the same number of boxes. But the fact remains that it is easier to book cargo on smaller ships, where 80% utilisation is not unusual. Load factors on ultra large container ships (ULCS) like HMM Algeciras rarely exceed 60%, and sometimes sail with significantly lower loads.

We assume, also, that HMM Algeciras will sail the most efficient possible route. This is dubious. Recently, large container ships have taken the Cape Route instead of through the Suez Canal, because burning 1,000 tonnes of additional fuel has been cheaper than paying the $3-500,000 toll.

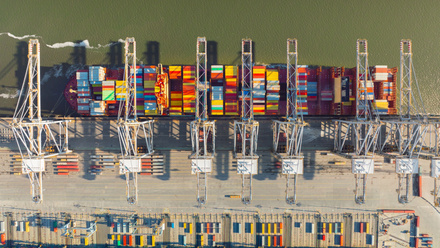

Ports are few and far between

And what of ports? Only a small number of ‘hub’ ports can make the massive investments needed for HMM Algeciras to call with a full load.

Constant dredging to maintain the necessary depth in port approaches and berthing areas is enormously costly, and environmentally damaging. New cranes must be installed with greater overreach to handle ULCS with 24 containers across their decks.

Does the placement of each hub deliver optimal hub-and-spoke efficiency? Who can say – after all, competing European hubs endlessly one-up each other in depth, capacity, and fee-reductions, regardless of whether they are well-placed to serve end-user demand.

Overtonnaged and overleveraged

So far, our ULCS business model does not appear especially robust. But taking the climate into account whittles it down even further. Mainstream media decry the emissions from ships, returning often to the adage that one ULCS emits ‘as much carbon as 50 million cars’ (whatever that means).

But this belies the real ground for criticism: namely, that ever-bigger giants displace the previous generation, which cascade down to trades that do not require them, leading to under-utilisation.

Owners must continuously scrap smaller vessels to feed their capacity cravings yet the environmental cost of this is almost never considered. Nor are the carbon implications of building a new ship; smelting, transporting, and welding together colossal quantities of steel, and spraying every square inch of them with VOC-based paint.

Nor, indeed, are the debts. In fuelling the acquisition of ever-bigger tonnage, the cumulative debt of fourteen major carriers reached $95bn as of Q3 2019, from $76bn in 2010, according to International Transport Forum figures. But there is nothing like a global economic crisis, such as the one presaged by COVID-19, to throw the madness into sharp relief.

Olaf Merk, a ports and shipping expert at the ITF, compares big shipping companies with Big Ag (agriculture), noting striking similarities. “In both agriculture and container shipping, policies – notably those of the European Union – are designed to pursue economies of scale,” he writes in Transport Policy Matters. “In agriculture the tool was subsidies; container shipping’s equivalent is the tonnage tax. Both sectors have special regimes that make them hybrids: market-driven sectors in name, but dependent on public support in practice.

“There is of course another major difference: agriculture is vital, [but] container shipping is essential to the extent that global trade is. With many world leaders pleading for more regional sourcing, long-range containerised transport might be less inevitable than thought – which opens the perspective for possible fundamental change.

Merk suggests we need to look to a future not necessarily based on the economies of scale, pointing out that “it has been stimulated by public policies – and these policies can change”.

Smaller could be better after all

There are certainly economies of scale in maritime, says shipping economist Martin Stopford, suggesting that coastal shipping could seize much more road and rail cargo in the coming decades by moving away from the hub-and-spoke, and towards a point-to-point model. Shipping is, after all, the most carbon-efficient of all transport modes by far, based on cargo carried.

Smaller, shallow-draught vessels would have much greater flexibility, able to call closer to the end user. “...It seems likely that in the coming decades there will be more interest in developing business to business (B2B) shipping services to link the outlying areas of regional economies, both in Asia, Europe and elsewhere,” Stopford writes in his ‘Three Maritime Scenarios 2020-2050’ report.

“Coastal shipping using UBER-style information technology to manage door-to-door transport will divert high-carbon cargo away from congested roads and rail to short sea shipping services. This will create a growing demand for small ships, but using the biggest small ships possible to obtain economies of scale.”

This could diminish emissions by as much as 100g of CO2 per tonne/km even before any work is done on replacing engines with low-or-zero-carbon alternatives. And smaller vessels on shorter voyages also provide the opportunity to develop these fuels and hybrid systems in the near term, as is already evident across a wide range of projects, notably in northern Europe.

“The short sea shipping industry will also provide the ideal testing ground for the new digital technology, including on-board systems; batteries; and semi-autonomous vessels,” Stopford says.

Charlie Bartlett is a freelance maritime writer.