Shipping’s ‘blame culture’ is a barrier to preventing accidents and deaths

When accidents happen onboard ships it is almost always the seafarer who pays the price – firstly by suffering injury or death in the accident, and secondly by usually being blamed for the incident.

We believe our great industry does itself, and those who work in it, a great disservice by pointing fingers in this simplistic way. We, and many others in the shipping industry, refer to this as a blame culture, and it must stop!

It is no surprise that this blame culture has developed. Today’s shipping industry is reliant on insurance provided by P&I Clubs. These not-for-profit mutual insurance associations provide cover for their shipowner and charterer members against third party liabilities arising out of the use and operation of ships. The system is geared towards attributing blame, in that cover is only applicable if someone is found to be the ‘guilty party’, in explanation for the cause of the accident. Effectively they insure owners and charterers against crew negligence amongst other factors.

So often, accident root causes are assigned due to crew being negligent, ignorant, or lacking necessary skills. We argue that this is not the case.

We believe the more pertinent questions to ask are:

-

Who is responsible for the employment of these crew members?

-

Who is responsible for the promotion of these crew?

-

Who decides that the training of these crew is adequate?

-

Who decides on the ship’s crew component, quality, and number?

-

Who is responsible for the onboard rules and regulations, and for the ship’s procedures?

-

Who checks whether ships and their managers/owners/operators comply with industry regulations?

-

Who is finally responsible for ensuring that those regulations are fit for purpose?

We all know where the answers to those questions should lie, yet the shipping industry does not routinely extend its accident investigation systems beyond the seafarer making a mistake. Crew pay the price and our great industry suffers reputational damage too.

Let us explain in more detail what we mean by using the example of accidents, often deaths, in enclosed spaces. Onboard ships these dangerous spaces present a threat to life for those working in them due to a potential lack of oxygen, the presence of hazardous fumes, and are hence correctly subject to strict procedures. Such spaces include: cargo spaces; double bottoms; fuel tanks; ballast tanks; cargo pump rooms; cargo compressor rooms; cofferdams; chain lockers; void spaces; duct keels; inter-barrier spaces; boilers; engine crankcases; engine scavenge air receivers; the vessel’s CO2 rooms; battery lockers; sewage tanks; and any adjacent connected spaces such as cargo space access ways or ‘Australian’ ladders.

In 2018 InterManager conducted an industry-wide survey where we asked the primary stakeholders, namely seafarers, one simple question: why do crew members die in enclosed spaces? More than 5000 seafarers responded, and one key response stood out; almost a third of seafarers responded to say that conflicting procedures, instructions, rules and regulations were at fault.

As a result, Intermanager dug deeper into what we, the shipping industry, know about enclosed space accidents. To their surprise, they discovered that we knew very, very little indeed. In addition, it seemed that PandI Clubs were reluctant to share their information. Out of thirteen requests for cooperation, only one provided some, limited, statistics.

As a result, InterManager began to collate their own statistics, as it seems that the problem is that the industry doesn’t recognise the extent of the problem.

The below chart demonstrates the issues clearly, and also highlights that seafarers were correct. In 2011 the IMO introduced Resolution A1050 which aimed to reduce the number of accidents in enclosed spaces (the red line). In fact, it seems to have had the opposite effect and more seafarers and stevedores now die in enclosed spaces than before A1050.

InterManager began collating its own statistics in 2018, as that was a particularly bad year when more than 40 people lost their lives in enclosed spaces. The problem clearly persists and up to September in 2023 we had already recorded 21 deaths.

So, it is clear that the introduction of resolution A1050 has not improved the situation. Nor have the many accident reports into these incidents identified a root cause? Nor have all the P&I clubs’ videos, posters, circular letters made enough of a difference to the statistics. In fact, following submissions from China with supporting papers from the HEIG and other concerned bodies, the IMO has now agreed to revise its enclosed space recommendations.

Why has this problem escalated and why have we reached this sorry state?

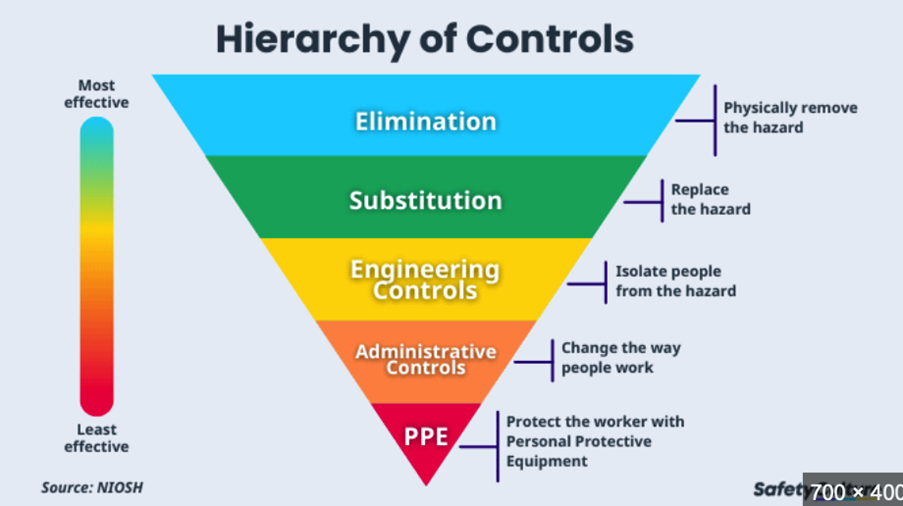

As seafarers pointed out – they believe that administrative controls are the biggest issue with enclosed space work. We have conflicting procedures and regulations. Indeed, we even refer to the spaces themselves in different terms; sometimes enclosed spaces, sometimes dangerous spaces, sometimes confined spaces.

Conflicting procedures can confuse crew and lead to accidents. For example, in relation to one space the procedure may say “enter only if the atmosphere is safe” but only a few paragraphs later, the same document may state that “if the atmosphere is not safe crew should use breathing apparatus” (BA). And then, in a further section of the same rules, crew may be reminded in bold capitals that BA SETS ARE ONLY TO BE USED ONLY IN AN EMERGENCY. So which instructions does the seafarer adhere to?

Seafarers can also receive very conflicting instructions, such as “all tanks to be ready by tomorrow morning”, when the reality is that the procedures required mean that is insufficient time to complete the task correctly. How can this goal be compatible with reality if the tanker has only six deck crew and there are 18 tanks?

In the InterManager survey, time pressure was identified by seafarers as a leading cause of enclosed space risk.

Another problem is that captains and other senior officers can feel the lack of authority to challenge such instructions, particularly if they are employed in a ‘hire and fire’ situation. Who wants to hear or read “not for re-employment” at their end-of-contract appraisal?

So, the ‘human element’ has to solve this conundrum itself and we think the results shown in these two graphs speak for themselves in terms of how effective that situation has proved to be.

So, coming back to blame culture, why are we concerned with how we investigate accidents today?

When we investigate an accident or a fatality we only do so up to the point when we find the ‘guilty party’. Why? Because many accident investigation courses are taught by police officers, where “this is the way we always have done it”. We don’t believe an accident investigation is entirely the same as a criminal inquiry. In addition, PandI Clubs insure owners against crew negligence, and therefore finding the “negligent party” can result in claim success.

Unfortunately, by doing it this way we miss a golden opportunity to learn valuable lessons. We blame and therefore we inhibit knowledge transfer.

Ship management companies can also miss the proverbial boat by concentrating on the ‘human element’ instead of supporting people who are actually calling for help. These are the people who are at the most risk and they are usually very keen to help to indicate system shortcomings. They have already experienced some of the root causes of the issues and if these are thoroughly considered, may result in “safety drift”.

The below picture illustrates safety drift:

We imagine, create, and describe the workplace as we wish it to be. Then time and financial pressures come into play, and we start seeing work done under time and financial pressures. Those pressures can, and do, cause our standards to buckle and drift. This situation is faced and confronted by our people, who try to resist this drift.

With deaths in enclosed spaces increasing, now is the time for action. In order to achieve the sought-after goal of zero deaths/accidents we must address all the issues outlined.

-

Regulations need to be amended to become clearer and more effective.

-

Pitfalls in procedures need to be removed.

-

Our regulatory and procedural frameworks must be rewritten to ensure they are consistent and easily understood throughout the international shipping industry, especially by the target audience.

-

We need to revise our approach to accident investigation, to examine why an accident occurred and clearly identify all the contributing factors. Saying that John made a mistake and was injured/killed is not the end of the investigation. We need to look at why John did what he did and really dig deep into the factors involved th,e regulations and procedures which were, or were not, adhered to or properly understood, and why not. It needs to be understood that no-one wants to get injured, or worse, all actually want to go home.

-

Ship owners, operators, managers, charterers, and office staff, need to properly understand the impact of their requirements on crew activities. If you demand all 18 tanks cleaned overnight by six crew, you need to realise fully what you are asking those crew to do, in this case cut corners and work at unrealistic speed.

We hope that accident investigators will concentrate on the drift not on humans. Would we then see the same accidents happening again and again?

We are all in this together and together we have a role to play in identifying and implementing the solutions. We all want an industry that is safe to work in and we all want to be proud of our industry’s safety record.

We hope we can successfully achieve this goal together; lives depend on it!