Quick crew response saves bulk carrier from disaster

Audible and visual alarms recommended following Hagen Oldendorff grounding – electrical failure blamed for disabling rudder angle indicators.

On a ship, it is a good idea to take nothing for granted. Unlike in the airline industry, equipment on a ship’s bridge and in the engine room is not standardised, meaning there is a greater chance that systems will not be installed or work as expected.

The case of the Hagen Oldendorff shows how the malfunction of a small piece of bridge equipment can lead to large issues, that without a quick response from crew, pilot and towage, could have been far worse.

On the morning of 9 April 2022, bulk carrier Hagen Oldendorff was making its way from the world's largest bulk export port, Port Hedland, Western Australia, up the access channel, with four tugs accompanying the vessel – two aft, and two shoulder tugs – as well as a pilot on board.

As the vessel passed by Hunt Point on the island of Finucane, the vessel began to navigate a tight turn to port. Shoulder tugs RT Atlantis and RT Inspiration cast off from the vessel, becoming passive rather than active escorts, with the aft tug remaining tethered.

By this time, considerable work had been undertaken between the Pilbara Ports Authority (PPA) and other groups to ensure that a safe towage regime was in place, and the eventuality of a blocked navigation channel was avoided, but the safety management system (SMS) left a lot of leeway as to how they could be deployed.

As the first one and then the other tug cast off, the vessel completed its turn. But then, something happened. At 01:37:49, crew on the bridge of Hagen Oldendorff overheard strange clicking sounds from the bridge electrical cabinet. Then, the vessel’s rudder angle indicator went dark.

With the indicator disabled while indicating dead-ahead, the crew had lost visibility of the rudder position, which was sending the vessel careening to port. As the pilot ordered stop engines and gave a sequence of rapid instructions to the tugs, the ship’s bow struck the side of the navigational channel and swung away to starboard.

Thankfully, by the time the pilot’s instructions had been completed, the vessel’s port side had hit the channel batter at a reduced speed of 6.1 knots. But the hull bottom had still sustained serious damage, including two breaches, and was taking on water. Structural members along the hull had buckled, and the transverse bulkhead between the tanks had failed, allowing water to freely pass between them.

The vessel was kept at anchorage for repairs, until departing for China on 18 May.

Tracking monitor issue

Both of the vessel’s six angle rudder indicators shared power supply, with a breaker situated in a junction box on the bridge. The loss of illumination prompted an assumption among pilot and crew that the vessel’s steering had been lost; the pilot’s instructions to the tugs were consistent with a steering failure.

What had actually happened, however, was that a tracking motor used to turn the vessel’s rudder angle indicator had burned out, which had caused a short-circuit localised to the bridge itself. Only the clicking sound alerted the crew to the fact that there was an issue, as no alarm had sounded. Subsequent investigation by Wah Kwong Ship Management HK found that 20 other ships in the fleet had a similar arrangement, with all rudder angle indicators on a single circuit.

What had not helped the situation was the decision to cast off the vessel’s shoulder tugs, which may have been able to assist the vessel in slowing the swerve to port.

Australian Transport Safety Bureau recommendations

Although the pilot’s actions, alongside those of tugs, ultimately stopped this incident from increasing in severity, the Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) stated: “The pilot had cast off the ship’s port and starboard shoulder tugs, which limited their ability to reduce the ship’s speed or to arrest the turn to port. The pilot’s decision to cast off these tugs was found to be inconsistent with the recommended practices of the port’s implemented escort towage strategy.”

In November 2022, following the incident, PPA updated the port user guidelines and procedures document to include the towage allocation and tug retention guidelines for outbound ships. Forward escort tugs would now be retained until the vessel was well clear of the bay.

Meanwhile, Wah Kwong Ship Management HK installed an audible and visual alarm to notify the crew in the event of a tripped breaker. CCTV was also installed on the bridge, to allow crew to physically monitor the rudder angle.

Tell us what you think about this article by joining the discussion on IMarEST Connect.

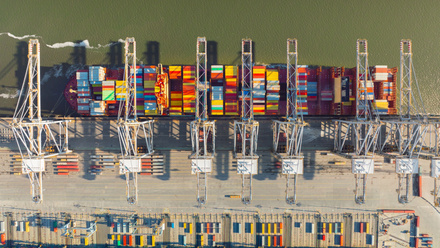

Image: a bulk carrier in Port Hedland, Western Australia; credit: Alamy.