Nearly one quarter of sea floor digitally mapped

We may all live on the blue planet, but there is still a lack of knowledge about the ocean despite Seabed 2030’s best efforts.

The Nippon Foundation and General Bathymetry Chart of the Ocean (GEBCO) joined forces in 2017 to build a high-resolution digital map of the world’s ocean floor by 2030, aptly named Seabed 2030. At that point, in 2017, only six percent of the sea floor had been mapped to modern standards.

“We’re now up to about one quarter of the sea floor mapped, so steady progress is being made,” say Stephen Hall, FIMarEST and Head of Partnerships for The Nippon Foundation and GEBCO.

This still leaves vast tracts of ocean that remain unmapped – and less than six years to go until 2030.

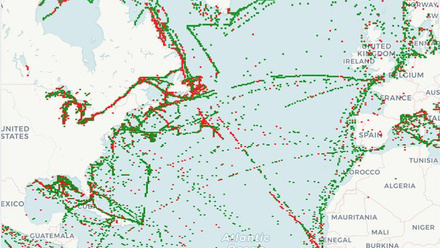

“Generally speaking, the biggest gaps are where people don’t go very often,” reasons Hall. “Large parts of the southern hemisphere sections of the Atlantic, Indian and Pacific oceans have very sparse data, usually along great circle routes between sea ports, or soundings taken en route to remote research bases in the Antarctica and Southern Ocean islands.”

The challenge to plugging these gaps is, simply, one of resource. There are a limited number of ships available with the equipment, time, trained crew, and funding to physically measure full ocean depth.

“You might think we could do it all quickly from space, but [even] with today’s technology, satellite remote sensing isn’t yet able to give us accurate measurements of ocean depth beyond the shallowest of waters as light or radar can’t penetrate far beneath the surface,” Hall explains.

“We can use variations in gravitational fields over great ocean trenches and mountain ranges to give us hints of the seabed shape from the vantage point of a satellite, but not at any level of fine resolution. So, we still need physical measurements from ships and uncrewed platforms such as autonomous survey vessels.”

Technology still key to reaching goal

Indeed, it seems that robots are our best hope when it comes to completing this task. “They are less expensive to operate than a ship with a human crew and some designs such as [those from] Saildrone can stay at sea for months, quietly gathering the data that we need,” says Hall, pointing out that autonomous systems can even help with hard-to-reach places such as under ice sheets.

Another short cut is to encourage those who already have seabed data to share it. “We believe that at least another 20 percent of the sea floor has already been mapped but is held in data vaults of governments and industries who so far have not been persuaded to share,” claims Hall, citing national security, commercial confidentially or jurisdictional conflicts as reasons why some datasets remain inaccessible. “Part of my role is to encourage the release of that locked-up data.”

At present, the 2030 goal looks like a stretch target, although Hall is keen to point out the timeline is less important than making steady progress towards the eventual objective. “It took over a century of measurements to obtain that first six percent, and only seven years to add nearly one fifth of the ocean floor,” he concludes. “Momentum is building, and as nations and industry begin to see the benefits of having better maps, we believe that the rate at which new data arrives will increase.”

Those benefits include improved marine spatial planning and maritime safety, better tsunami warning systems, more accurate digital twins and ocean models, and keeping the UN Ocean Decade for Sustainable Development on track.

Hall presented Seabed 2030 at Ocean Decade 2024 in Barcelona and the Our Ocean Conference in Athens, where he noted a growing appreciation of the benefits of sharing data, with several industry bodies coming forward offering data to build the higher-resolution seabed maps that will help with the sustainable stewardship of our beautiful blue planet.

Tell us what you think about this article by joining the discussion on IMarEST Connect.

Main image: ocean seabed; credit: Shutterstock.

Inline image: Stephen Hall, FIMarEST; credit: Stephen Hall.