In depth: The mighty benefits of nuclear reactors in submarines

A new partnership between Australia, the UK and US – named AUKUS – requires submarines to operate for a remarkable 33 years without refuelling. For this, they will need to use highly enriched uranium.

As the UK and US help Australia in acquiring nuclear-powered submarines as part of Project AUKUS, the role of nuclear reactors in submarines is once again in the spotlight.

Rolls-Royce, who produces the PWR2 submarine reactor for the Astute-Class nuclear submarines, states: "A small spoonful of uranium is all it takes to power a fully-submerged submarine on a full circumnavigation of the world.”

But how can such a small amount of material power a submarine that far and how does it work?

Like many elements, uranium comes in different variants called isotopes. Nuclear reactors need uranium-235. However, natural uranium mined from the ground primarily consists of uranium-238 mixed with small amounts of uranium-235.

To make the reactor operate efficiently and safely, the percentage of uranium-235 needs to be increased through a process called enrichment. For the AUKUS submarines, this enrichment level typically falls between 93% and 97%.

Inside the reactor pressure vessel, the uranium-235 is bombarded with neutrons, causing some of the nuclei to undergo nuclear fission. A moderator material such as water, heavy water or graphite in the core slows the neutrons released from fission.

By moderating the flow of neutrons, more fission events will occur, creating a nuclear chain reaction that generates heat. This heats the water circulating in the primary loop. For the nuclear reactor to function, the heated water in the primary loop needs to be kept at a temperature of approximately 300°C.

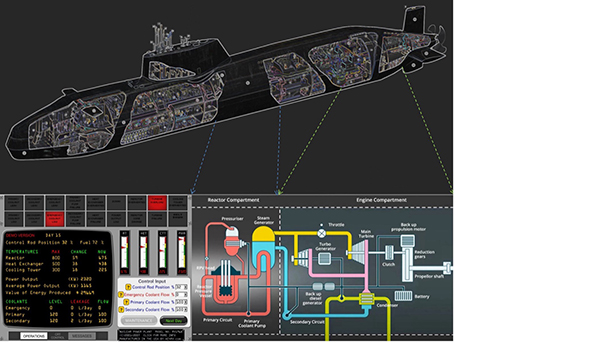

Astute-class nuclear submarine reactor and engine, The Royal Institution of Naval Architects

The hot water in the primary circuit is then fed into steam generators connected to a secondary circuit. This passes through dryers on its way to drive turbines. The turbines are connected to the propellers via a clutch and gear arrangement, as well as electricity generators, causing them to turn at high speed.

Spent steam at low pressures runs through condensers, which are cooled by seawater. This cooling causes the steam to condense into liquid water, which is then pumped back into the steam generators, continuing the cycle. Any water lost during this process is replaced with desalinated seawater.

Uranium-blocking control rods inserted between the uranium-235 rods are used to control the rate of the chain reaction. They absorb neutrons, reducing the number available to sustain a chain reaction. In emergency situations, these rods can be fully inserted into the reactor pressure vessel to halt the nuclear reaction rapidly. This is known as a Safety Control Rod Axe Man (SCRAM) event.

Submarines represent a special opportunity for nuclear

Submarines are a unique and extreme operating environment. Designed to be submerged for up to six months at a time (in the case of nuclear submarines) but with limited oxygen, the potential of using diesel engines for propulsion for long durations and at depth is limited at best.

Diesel engines require oxygen for combustion and produce exhaust gases, including carbon dioxide, which needs to be expelled through a process called snorting. Oxygen generators can assist by producing oxygen from water through electrolysis, yet non-nuclear submarines still need to surface to replenish their oxygen supplies for both the crew and engines.

Current diesel submarines are also limited to speeds of 20 knots (37km/h). The Collins-class maximum submerged duration is just 70 days. With the introduction of nuclear power, historically slow underwater vessels were transformed into warships capable of sustaining speeds of 30 knots (56km/h) alongside longer submersion times.

Achieving speeds of 30 knots is important for outmanoeuvring potential threats, including hostile submarines and surface ships tasked with hunting submarines.

A key strategic advantage of nuclear submarines is their ability to survive a first-strike attack. Their capacity to remain undetected while submerged serves as a powerful deterrent, discouraging the outbreak of hostilities in the first place.

And as these nuclear submarines’ shelf life is placed at 33 years, it means these strategic advantages are being developed to achieve long-term goals.