Has naval engineering reached its ‘Fisher’ moment?

Rear Admiral Steven McCarthy, the UK Royal Navy’s most senior engineer, was a keynote speaker at the International Naval Engineering Conference (INEC) last November. Here he shares why he believes we have reached a critical juncture in the field.

We are at a Nexus – rising geopolitical tension, medium-scale conflict, significant fiscal deficit, and decreased military spend combined with the need to re-arm for different ways of fighting. In fact, some commentators have remarked that we’re at a ‘Fisher’ moment. Admiral Sir John "Jacky" Fisher was first sea lord in the early part of the 20th century and understood that the Royal Navy must continue to evolve if it were to remain a global power.

As the age of the wooden ship gave way to steel and steam, it was Fisher’s vision and determination that is credited with modernising the Royal Navy. His crowning achievement was the introduction of the Dreadnought - a ship that revolutionised naval warfare and rendered every other battleship in the world obsolete.

Here, I’d like to explore that theme from a Naval engineering and a technology perspective; to enquire whether we’re modernising quickly enough, and if we have a ‘Dreadnought’ on the drawing board?

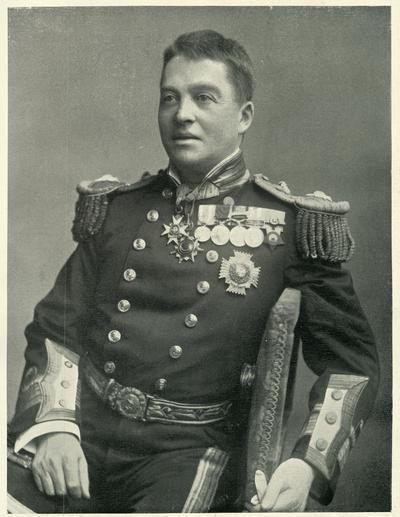

Admiral Sir John "Jacky" Fisher transformed the Royal Navy early in the 20th Century.

One thing’s for sure; the imagination, skills and productivity of the science, technology and engineering community will remain in high demand. The skills we need to overmatch the growing threats of cyber warfare, AI, edge computing, and data denial need to be in active formation right now.

To meet this need, the Royal Navy has embarked on a generational fleet renewal with new UK-designed and built submarines, frigates, mine hunting and seabed warfare capabilities, fleet solid support and multi-role support ships to complement new Aircraft Carriers, and updated Air Defence Destroyers.

But the revolution of Dreadnought was a long time in gestation. It was the aggregation of the product of generations of development and continuous improvement. It was built on the backs of generations of naval engineers and naval architects.

For instance, we’ve not crossed the threshold to truly capitalise on uncrewed systems, advanced submarines, artificial intelligence, and cyber warfare capabilities. There’s a missing ingredient, and perhaps a peace dividend, that has kept a transformational change at arm’s length.

Our circumstances are different to Fisher’s, but I would agree with his overarching concern that the Royal Navy must continue to be more agile and efficient. Innovation is not just about the tools we use; it is about creating a mindset of adaptability and foresight. It’s about understanding the potential of your systems, and exploiting that potential.

Efficiency and effectiveness must go hand in hand. Our autonomous mine hunting capability is a helpful example here – in one stroke we’ve removed people from mined areas, accelerated our mine detection and route clearance, and substantially changed the numbers and skills of the workforce to deliver this essential and enduring capability requirement.

But I argue that Naval engineers are still underrepresented as expert technologists in the innovation cycle that gets us to our Dreadnought.

The battles of tomorrow will be fought as much with algorithms and data, as with missiles and ships, and we must ensure that our workforce is prepared for this reality. We need a workforce of digital natives with the spark and imagination to defeat emerging threats, as well as the gumption to spot the trends and flaws in the operational analysis they perform. Their ability to integrate complex systems and think on their feet will be crucial to maintaining our operational advantage.

And so, diversity was never more important in our workforce. Today’s Royal Navy is a more inclusive force, drawing talent from all backgrounds and walks of life. In a world where threats are constantly evolving, it’s vital that we keep diversifying so that we can think creatively and approach problems from different angles.

Our success will also be defined by our willingness and ability to work together and trade the skills, knowledge and mutual professional recognition to find the balance between what the Royal Navy does and what industry can deliver. As Alan Turing, Margaret Hamilton (my hero of Apollo Code fame) and many others have taught us, there’s no monopoly on or limit to imagination and no formula for success. It’s how we engage, encourage, include and inspire that ultimately leads us to victory.

We must be willing to make choices linked to design intent and limited by system performance and reconfigurability. I argue that our Fisher moment must make this doctrinal leap – when might we give up the ship?

To conclude, I reflect on what Fisher’s protege Admiral Sir John Jellicoe tells us in his Battle of Jutland Despatch of 1916: ‘It must never be forgotten, however, that the prelude to action is the work of the engine-room department…... The qualities of discipline and endurance are taxed to the utmost under action conditions…Failures in material were conspicuous by their absence, and several instances are reported of magnificent work on the part of the engine-room departments of injured ships…The artisan ratings also carried out much valuable work during and after the action; they could not have done better.’

When our turn comes – as it may – let’s commit to being certain that we too could do no better.

Join the conversation on IMarEST Connect, our member-only forum.